Trefoil Integrity

Trefoil Integrity was the coalition of GS members, especially delegates; across Northeast Ohio who believed in the democratic process as outlined in the GSUSA constitution. In spite of being from different camps, they refused to compete with each other. Instead, they worked together trying to protect the rights of GS membership and trying to preserve outdoor experience as a basic part of Girl Scouting.

Girl Scout members file lawsuit seeking to stop sale of camps

Staff Writer

Akron Beacon Journal

3-10-2012

A lawsuit seeks to stop the Girl Scouts of North East Ohio’s controversial effort to sell four campsites.

The suit, filed Friday in Carroll County, asks the court to force the board of directors to recognize a vote that was taken by the organization’s general assembly that stopped the sale and required a new analysis of the group’s needs, with future action to be decided by a majority of the membership. Lynn Richardson of Richfield, president of Trefoil Integrity, a group of adult Girl Scouts that raised $20,000 to hire a lawyer and file the suit, said the Northeast Ohio council’s “code of regulations” makes the organization’s membership the final authority on such matters.

However, the board ignored a motion approved by 60 percent of the membership and is still looking for buyers for four camps, including Crowell/Hilaka in Summit County’s Richfield Township.

Girl Scouts of North East Ohio’s leadership has said it needs to sell four of the seven camps it operates in an 18-county region because they are too costly to keep. Since 2009, the organization has sold or returned seven other camps to their owners. If its plans are completed, the council will have only three of the 14 camps that existed four years ago. News of the filing came too late Friday to reach officials at Girl Scout’s headquarters, but organization leaders have addressed the need to close the camps in the media.

Joan Villarreal, chairwoman of the Girl Scout’s board of directors, said in a recent editorial that the seven current camps need a combined $18 million in repairs and improvements. “The reality is, if our properties had been maintained properly for the past 25 years or more, and more Girl Scouts were using our camps, the decision to divest of properties would not have been necessary,” she wrote. “The board believes the Girl Scouts deserve better than minimally acceptable camps. We need to provide outstanding facilities that offer additional types of programming and that are safe, environmentally friendly and accessible.”

But members have fought back, filling meetings, staging protests, signing petitions and trying to raise $50,000 for court action through the website www.trefoilintegrity.org. “When we got to $20,000, we knew we had enough to hire a lawyer and get the ball rolling, but we need more money to be able to defend that,” Richardson said. The group is represented by Hamilton DeSaussure Jr. of the law firm Day Ketterer in Hudson. Richardson said selling the camps “is going to destroy the council.” More than half of the Girl Scouts use the camps, she said.

“It’s important that if you are taking away something that is the flagship program of the organization, which for Girl Scouts is camping, the decision needs to be made carefully,” she said. “The information [the board] used to come up with this idea was grossly inaccurate.”

In addition to stopping the sale and getting the board to honor the general assembly’s vote, the lawsuit seeks to enforce the membership’s right to add three directors to the board. Richardson said Girl Scouts of North East Ohio’s regulations allow the board of directors to number between 15 and 20, elected by the membership. Currently, there are 17 board members. The suit contends that members should have been permitted to vote on whether to elect the maximum of 20 directors last year, but the board would not allow the vote. “They basically just made up a rule on their own,” she said. “The Girl Scouts is a democratic process. It’s about what the members want.” Richardson said the court case should reveal what the four camps are valued at, as well as the value of the other seven sites that were sold or returned to their owners. Ohio law states a nonprofit organization cannot divest itself of more than 50 percent of its assets without approval of the membership, Richardson said.

Divesting itself of 11 of 14 camps “might put us past the 50 percent mark, so that needs to be looked at,” Richardson said.

Paula Schleis can be reached at 330-996-3741 or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at http://twitter.com/paulaschleis.

Staff Writer

Akron Beacon Journal

3-10-2012

A lawsuit seeks to stop the Girl Scouts of North East Ohio’s controversial effort to sell four campsites.

The suit, filed Friday in Carroll County, asks the court to force the board of directors to recognize a vote that was taken by the organization’s general assembly that stopped the sale and required a new analysis of the group’s needs, with future action to be decided by a majority of the membership. Lynn Richardson of Richfield, president of Trefoil Integrity, a group of adult Girl Scouts that raised $20,000 to hire a lawyer and file the suit, said the Northeast Ohio council’s “code of regulations” makes the organization’s membership the final authority on such matters.

However, the board ignored a motion approved by 60 percent of the membership and is still looking for buyers for four camps, including Crowell/Hilaka in Summit County’s Richfield Township.

Girl Scouts of North East Ohio’s leadership has said it needs to sell four of the seven camps it operates in an 18-county region because they are too costly to keep. Since 2009, the organization has sold or returned seven other camps to their owners. If its plans are completed, the council will have only three of the 14 camps that existed four years ago. News of the filing came too late Friday to reach officials at Girl Scout’s headquarters, but organization leaders have addressed the need to close the camps in the media.

Joan Villarreal, chairwoman of the Girl Scout’s board of directors, said in a recent editorial that the seven current camps need a combined $18 million in repairs and improvements. “The reality is, if our properties had been maintained properly for the past 25 years or more, and more Girl Scouts were using our camps, the decision to divest of properties would not have been necessary,” she wrote. “The board believes the Girl Scouts deserve better than minimally acceptable camps. We need to provide outstanding facilities that offer additional types of programming and that are safe, environmentally friendly and accessible.”

But members have fought back, filling meetings, staging protests, signing petitions and trying to raise $50,000 for court action through the website www.trefoilintegrity.org. “When we got to $20,000, we knew we had enough to hire a lawyer and get the ball rolling, but we need more money to be able to defend that,” Richardson said. The group is represented by Hamilton DeSaussure Jr. of the law firm Day Ketterer in Hudson. Richardson said selling the camps “is going to destroy the council.” More than half of the Girl Scouts use the camps, she said.

“It’s important that if you are taking away something that is the flagship program of the organization, which for Girl Scouts is camping, the decision needs to be made carefully,” she said. “The information [the board] used to come up with this idea was grossly inaccurate.”

In addition to stopping the sale and getting the board to honor the general assembly’s vote, the lawsuit seeks to enforce the membership’s right to add three directors to the board. Richardson said Girl Scouts of North East Ohio’s regulations allow the board of directors to number between 15 and 20, elected by the membership. Currently, there are 17 board members. The suit contends that members should have been permitted to vote on whether to elect the maximum of 20 directors last year, but the board would not allow the vote. “They basically just made up a rule on their own,” she said. “The Girl Scouts is a democratic process. It’s about what the members want.” Richardson said the court case should reveal what the four camps are valued at, as well as the value of the other seven sites that were sold or returned to their owners. Ohio law states a nonprofit organization cannot divest itself of more than 50 percent of its assets without approval of the membership, Richardson said.

Divesting itself of 11 of 14 camps “might put us past the 50 percent mark, so that needs to be looked at,” Richardson said.

Paula Schleis can be reached at 330-996-3741 or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at http://twitter.com/paulaschleis.

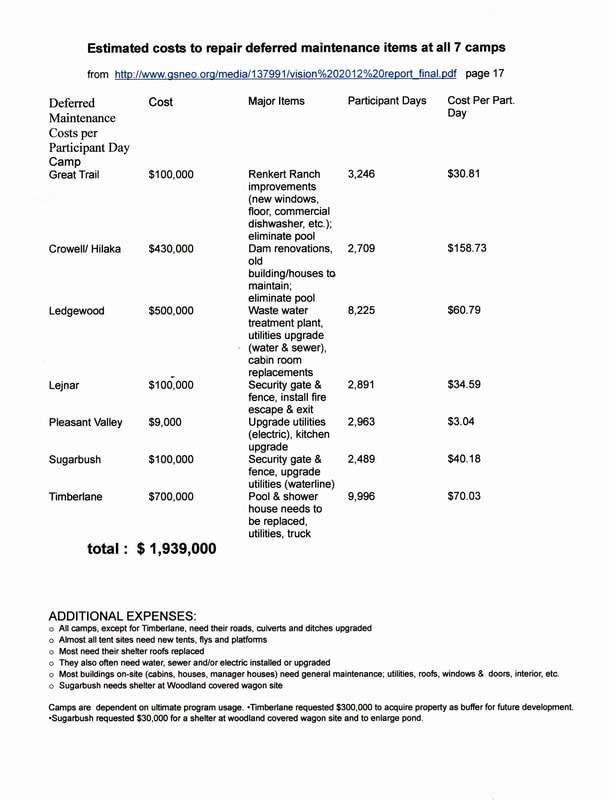

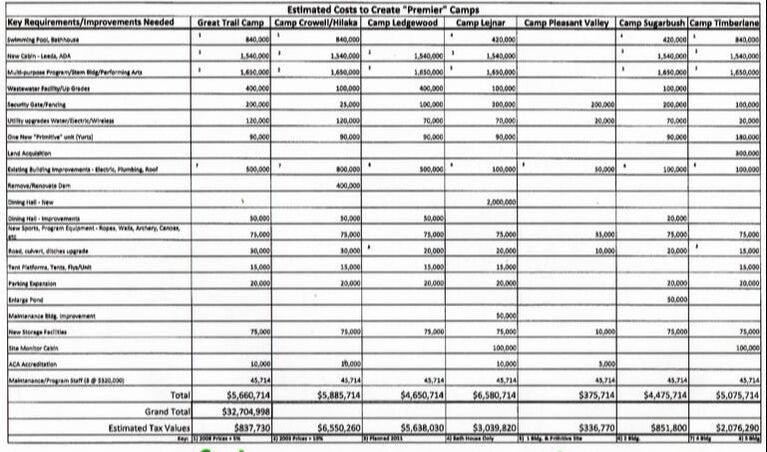

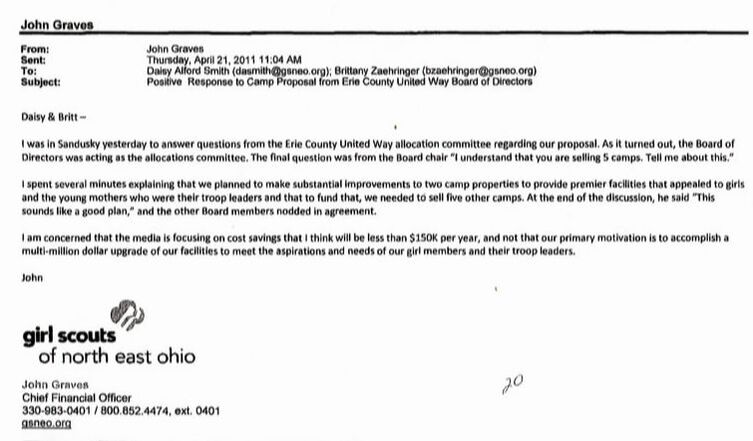

Following the money

The "Vision 2012" Task Force compiled a total, itemized repair bill jut shy of Two Million dollars for all seven remaining camps. When the sale of five camps was announced in 2011, Council spokesman Brent Gardner justified it by telling the General Assembly that it would cost $30 MILLION to repair the camps - a figure he repeated for various media outlets. In the Akron Beacon Journal article above, GSNEO board president Joan Villareal quotes $18 million. Meanwhile, the Chief Financial Officer denied that it was a financial necessity at all, but a choice for shiny new "premier facilities"!

How GSNEO redefined what it meant to be a Girl Scout.

“The ultimate responsibility for the Girl Scout Movement rests with its members. We govern by an efficient and effective democratic process that demonstrates our leadership in a fast-changing world.” -from the preamble to the GSUA constitution

How this played out in GS of NE Ohio:

The democratic process was blocked at several stages. Members were denied a voice in the most significant decision of the council. National allowed this to happen and the courts upheld it. GSNEO is now a paradox: a girl’s leadership organization that refused to acknowledge what its own girls told them and that disregarded member participation.

A Tale of Two Meetings.

in 2009, Girl Scouts of North East Ohio (GSNEO) held two General Assembly meetings every year to take care of council business through democratic process. Delegates to the Assembly were elected by county from registered Girl Scouts age fourteen and up.

With the merger which formed GSNEO in 2007, the delegates knew that some of their fourteen camps might be closed. After the first round of camp closures in 2009 (seven closed permanently, two “mothballed” for further study),the council Board of Directors set up a detailed evaluation of the remaining camps. This detailed study was named "Vision 2012" Members from each camp were invited to help with the research. Costs, facilities, usage patterns, and member preferences were all to be considered. The most significant finding from the study was that the camp usage numbers were actually much higher than had been previously reported. The council had been saying that only 5% of the membership used the camps. When the actual usage numbers were shared with Vision 2012, it became apparent that the actual percentage was about 55%- which made sense, since a large proportion of the membership consisted of Daisies who were too young to camp. The majority of girl members eligible to go camping did use the camps. The 5% figure was only the percentage of girls who attended council-sponsored programs. This information should have had a significant impact on the board's decision. It didn't.

Meeting 1

At the 2011 spring Assembly, the Board of Directors announced their final decision: five more camps would be sold - including the top-ranked favorites. The two remaining camps would be re-branded as “Premier Leadership Centers”.

The announcement had leaked to some of the delegates in advance, although few could believe the rumors were true. It was no longer a question of being disappointed if a favorite camp was not kept. The loss of so many camps all at once would have a devastating effect on Girl Scouting. As the Assembly listened to board spokesman Brent Gardner, it became apparent that the points being used to justify the decision did not jibe with the results of the council-sponsored camp survey or the cost estimates released in the council report on camps. Gardner said they had crunched all the numbers, and there was no other possible solution.

The Assembly was given fifteen minutes for questions. Girls went to the microphone in tears, pleading for camps - not leadership centers or hotels. Troop leaders demanded to know what alternatives the board had considered. Parents asked how their daughters’ troops could realistically function without local camps. Delegates who worked on the study questioned the discrepancies. Petitions were read. Edie Dale of Twinsburg brought a list of the campsite capacities and proceeded to show how two camps were not enough for 40,000 girls. The Chairman said they would be turning capacity issues over to the staff to work out. Delegate Corey Ringle from Shaker Hts. motioned for a resolution to re-evaluate.

Corey’s resolution:

Since the merger of five legacy councils to form Girl Scouts of North East Ohio, there has never been a time when the membership had all of the following occur at the same time:

1. Fully open camps

2. Readily available information on all the GSNEO camps

3. A centralized, easy to use, campsite registration process.

During the first two years the camps were fully open, but there was no camp information on the council website. Many members did not know they were allowed to camp outside their own region. If they did know, the separate regional applications were a barrier. This limited program options and impeded the unification of the council. By the time the latter two factors were corrected, half of Great Trail and most of Crowell Hilaka had been closed. Because of these circumstances, assessment of GSNEO property usage has always been made during restricted conditions.

Mindful that the property decisions made now will impact the health of GSNEO for generations to come, they should not be made with undue haste. A full evaluation of council programming needs - including camp usage - should be made which includes all available sites , a user-friendly reservation process, and full details on first choice preferences and alternative plans. This will determine what it is that girls and their parents truly want.

During this evaluation

Cognizant of the important role of camping as the signature activity of Girl Scouts of North East Ohio, and the degradation caused by a policy of preemptive neglect by certain legacy councils; priority in the council budget will be directed to outdoor programming at our camps during this trial period. To defray expenses and support member services, the camps should be used for additional programming: journey steps, volunteer training, service unit events during the week, etc. whenever possible. We recognize that with the increase in council membership, we are in a good position for such a comprehensive study.

Corey’s resolution was seconded – and ignored. Shortly afterwards, the Assembly was dismissed. Brent Gardner told a reporter in the lobby that the uproar inside the meeting was just a small, vocal minority. The silent majority of the council membership supported the board’s plan.

Member response

For the rest of the spring and the following summer, members wrote letters to the board, to the national office, to the media. Petitions were distributed. “Camp-In”s were held on the lawn of the council headquarters in Macedonia. The Board insisted that girls of the future wanted versatile spaces with science and computer labs. Protesters questioned how GSNEO, with its poor track record of online registrations and data collection, could think of trying to position itself as cyber and science experts. But anyone questioning the board property plan was discredited as nostalgic and emotional. The Board plan was “a done deal” for moving forward.

When it became clear that the board would not re-consider, a group of delegates led by Gwenn Kolenich and Roberta Riordan began investigating what actions were open through the official Girl Scout democratic process. Various experts were consulted and options weighed. One option was to impeach and replace the board. But fears of de-stabilization made that a last resort.

A parliamentarian told the delegates that the reason Corey’s resolution was ignored was that she had not followed the correct procedure. She should have motioned for a change to the agenda at the beginning of the meeting to allow “new business” to be discussed. Then she could have introduced her resolution. Roberta began studying parliamentary procedure. Gwenn reviewed the GSNEO code of regulations and found that a majority of the General Assembly could call a special meeting to take action on an issue. She began drafting a special meeting agenda.

The delegates affirmed that they would not demand that certain number of camps be kept. They just wanted the decision to be reviewed with the understanding that girls wanted to camp, and that camping had value. They wanted to have accurate usage data, realistic cost projections, and member input. They wanted it understood that although the council subsidized camping by nearly a million dollars per year, members in turn subsidized the council through $8 million of cookie sales in an $11 million annual budget.

There was no way for the delegates to independently check the accuracy of council-generated data other than internal consistency and the delegates’ own observations. Therefore, it was decided that the criteria for acceptance of a property plan would simply be approval by the General Assembly. Working with a lawyer, the delegates drafted two resolutions. One was an amendment that would require all future property sales to have the approval of 2/3 of the General Assembly. If the amendment passed, and the board refused to accept it, then the delegates would move to impeach. If the board showed themselves willing to accept the will of the majority, then they could stay.

However strong an amendment might be, it would not affect the plan that they had already announced. There would need to be a resolution addressing the immediate crisis. The general understanding of GS governance was that “delegates influence, the board decides.” In other words, the delegates could not tell the board what to do, but the board was obligated to consider the wishes of the delegates. In response to Brent Gardner’s statement that the majority of the members supported the board, they needed a clear statement that the delegates did not accept the board’s property plan. This statement was drafted as the first resolution:

The present Membership Delegates will vote on a resolution requesting that the Board of Directors immediately cease and desist all activities in connection with the transfer of any real property held in the name of the Girl Scouts of North East Ohio, until such time as any such pending, anticipated or planned transfers may be approved by a vote of two-thirds (2/3) of the voting members of the General Assembly participating and voting at a meeting held pursuant to Article II, Section 3 of the Code.

The delegates and other volunteers began circulating the request for the special meeting. About half of the needed signatures were obtained right away. The council office refused to provide contact information for the others to forward the request for signatures to them. The delegates were located one by one throughout the following summer.

As time passed, Roberta became concerned that they might not be able to find enough delegates to sign the special meeting request. She wrote a slightly different version of the amendment to submit for the regular meeting of the General Assembly in October. The Council Chief Operation Officer told her that she could not submit a resolution because the procedure for submission had not been established. Roberta submitted it anyway using the national procedure.

The 51st signature for the special meeting was obtained on September 29th. The signed request was delivered to the council office the next day. The board chair had 30 days to call the meeting and he chose to schedule it immediately prior to the regular Fall General Assembly on October 29th.

The formal call to meeting was mailed out from the council office which included the agenda of the special meeting and Roberta’s resolution in the regular meeting. As per usual, there was a single slate of candidates proposed for the Board of Directors by the Board Development Committee. The only way to have alternatives from the BDC slate was to nominate candidates from the floor. But GSNEO code required that floor nominations submit applications in advance with three endorsements from current assembly members. Pro-camp and pro-democracy candidates who had been rejected from the slate of board re-applied to be candidates nominated from the floor.

MEETING 2

Chairman Dan Bragg started the meeting by instructing the delegates that they could only speak once on each topic, for no more than one minute. Roberta objected, citing parliamentary procedure which permitted each delegate to speak twice for up to ten minutes each time.

Proponents of the resolutions reminded the Assembly that that they were asking for a realistic re-evaluation of a disastrous camp plan.

Opponents complained that they had been bullied by numerous messages and argued that only the board – not the average member- had the financial qualifications to make important business decisions for the council.

Debate proceeded until the chairman called for the Assembly to vote on the first resolution. It passed 52-35; 60% of the vote.

The quorum report just prior to the vote was:

12 Directors

1 Girl Director

6 Board Development Committee Members

5 National Delegates

63 Membership Delegates

With this clear message that the majority of the membership supported re-evaluation, the board finally had definitive information on membership opinion. But it made no difference. The vote did not change when it came to a permanent amendment to protect the rights of the members: 60% in favor. Not enough to pass an amendment which required a 2/3 majority.

Since the amendment failed, the question of board acceptance was moot, as was impeachment. During the regular meeting, Roberta presented a brilliant explanation for her version of an amendment. The vote was slightly higher in favor, but not up to the full 2/3 majority needed to pass.

Unexpected controversy rose during the election of board members. Although there were eight vacancies on the board, the chairman declared that only five seats were to be filled. Delegates pointed out that the code of regulations said nothing about restricting elections. Delegate Barbara Parkinson read the pertinent sections out loud to the Assembly. But the head of the BDC, the board chair, the parliamentarian, and the council lawyer all refused to allow a full election. Dan Bragg declared that any ballot with more than five names marked would be disqualified.

* * *

In the focus on the amendments and the dismay over the restricted election, the delegates did not immediately realize the significance of the vote on the first resolution. They had only asked that the membership delegates vote on it in order to give the board of directors clar knowledge of overall membership opionion. But instead, the chairman had directed the entire Assembly to vote on it. And the entire Assembly passed it.

What did this mean? True, it would have been stronger if one of the amendments had also passed. But if council democratic process had any value at all, then passage of this resolution to cease and desist from property sales without approval of the Assembly had to be considered as a valid directive. This was brought to the board’s attention.

The board refused to honor the successful resolution.

The members formally asked GSUSA to intervene - in the belief that the national organization would uphold democracy as the foundation of the Girl Scout movement. GSUSA refused because the request had not come from the council board or CEO.

The members then took the issue to court.

How the legal action played out

- the 2011 GSNEO board election had indeed been improperly restricted, and there was enough of a basis to take the case to trial.

Was there anything that could have changed the outcome?

During Vision 2012, GSNEO received two generous offers for conservation easements that would have allowed them to maintain two of the camps. One was for Crowell Hilaka in Summit County offered by the Western Reserve Land Conservancy, which was a direct response to the camp's closure. The other was for Camp Lejnar in Lake County made by the Lake County Metroparks. This had been in the works for a long time. In both cases, GSNEO informed the donors that acceptance of such arrangements would "impair the integrity of the Vision 2012 process". Everything had to be put on hold until after the final decisions were made.

At about the same time that the conservation easements were being rejected, Camp Ledgewood broke ground for a new observatory. When members asked how a major new construction project fit in with the supposed "integrity of the Vision 2012 process", the GSNEO board and staff replied that they couldn't help it. They had gotten a grant for the observatory and had to use it.

Millions of dollars in conservation easements- rejected. New construction elsewhere- accepted. Member surveys strongly in favor of keeping camps - ignored. The evidence suggests that the camp decision was a forgone conclusion. The legacy councils that came to the merger with healthy bank accounts knew they would be allowed to keep their camps. As for the others: GSNEO invested much time and energy trying to give the appearance of careful judgments with member input. But it's likely that no amount of money, member support, or public opinion could have made any difference.

(Trefoil Integrity was the coalition of GS members, particularly delegates, across the northeast Ohio council who believed in the democratic process as outlined in the GSUSA constitution. In spite of being from different camps, they refused to compete with each other. Instead, they worked together trying to protect the rights of GS membership and trying to preserve outdoor experience as a basic part of Girl Scouting.)

“The ultimate responsibility for the Girl Scout Movement rests with its members. We govern by an efficient and effective democratic process that demonstrates our leadership in a fast-changing world.” -from the preamble to the GSUA constitution

How this played out in GS of NE Ohio:

The democratic process was blocked at several stages. Members were denied a voice in the most significant decision of the council. National allowed this to happen and the courts upheld it. GSNEO is now a paradox: a girl’s leadership organization that refused to acknowledge what its own girls told them and that disregarded member participation.

A Tale of Two Meetings.

in 2009, Girl Scouts of North East Ohio (GSNEO) held two General Assembly meetings every year to take care of council business through democratic process. Delegates to the Assembly were elected by county from registered Girl Scouts age fourteen and up.

With the merger which formed GSNEO in 2007, the delegates knew that some of their fourteen camps might be closed. After the first round of camp closures in 2009 (seven closed permanently, two “mothballed” for further study),the council Board of Directors set up a detailed evaluation of the remaining camps. This detailed study was named "Vision 2012" Members from each camp were invited to help with the research. Costs, facilities, usage patterns, and member preferences were all to be considered. The most significant finding from the study was that the camp usage numbers were actually much higher than had been previously reported. The council had been saying that only 5% of the membership used the camps. When the actual usage numbers were shared with Vision 2012, it became apparent that the actual percentage was about 55%- which made sense, since a large proportion of the membership consisted of Daisies who were too young to camp. The majority of girl members eligible to go camping did use the camps. The 5% figure was only the percentage of girls who attended council-sponsored programs. This information should have had a significant impact on the board's decision. It didn't.

Meeting 1

At the 2011 spring Assembly, the Board of Directors announced their final decision: five more camps would be sold - including the top-ranked favorites. The two remaining camps would be re-branded as “Premier Leadership Centers”.

The announcement had leaked to some of the delegates in advance, although few could believe the rumors were true. It was no longer a question of being disappointed if a favorite camp was not kept. The loss of so many camps all at once would have a devastating effect on Girl Scouting. As the Assembly listened to board spokesman Brent Gardner, it became apparent that the points being used to justify the decision did not jibe with the results of the council-sponsored camp survey or the cost estimates released in the council report on camps. Gardner said they had crunched all the numbers, and there was no other possible solution.

The Assembly was given fifteen minutes for questions. Girls went to the microphone in tears, pleading for camps - not leadership centers or hotels. Troop leaders demanded to know what alternatives the board had considered. Parents asked how their daughters’ troops could realistically function without local camps. Delegates who worked on the study questioned the discrepancies. Petitions were read. Edie Dale of Twinsburg brought a list of the campsite capacities and proceeded to show how two camps were not enough for 40,000 girls. The Chairman said they would be turning capacity issues over to the staff to work out. Delegate Corey Ringle from Shaker Hts. motioned for a resolution to re-evaluate.

Corey’s resolution:

Since the merger of five legacy councils to form Girl Scouts of North East Ohio, there has never been a time when the membership had all of the following occur at the same time:

1. Fully open camps

2. Readily available information on all the GSNEO camps

3. A centralized, easy to use, campsite registration process.

During the first two years the camps were fully open, but there was no camp information on the council website. Many members did not know they were allowed to camp outside their own region. If they did know, the separate regional applications were a barrier. This limited program options and impeded the unification of the council. By the time the latter two factors were corrected, half of Great Trail and most of Crowell Hilaka had been closed. Because of these circumstances, assessment of GSNEO property usage has always been made during restricted conditions.

Mindful that the property decisions made now will impact the health of GSNEO for generations to come, they should not be made with undue haste. A full evaluation of council programming needs - including camp usage - should be made which includes all available sites , a user-friendly reservation process, and full details on first choice preferences and alternative plans. This will determine what it is that girls and their parents truly want.

During this evaluation

- GSNEO should retain all current properties.

- All campsites that are safe for usage shall be opened for use (with the possible exception of a rotation of winter closures for energy conservation).

- Members will be encouraged to form or join Friends groups for each of the properties to assist with support and minor maintenance.

- GSNEO will budget adequate funds for maintenance at each site to prevent property deterioration and to maintain safety standards.

- GSNEO funds may be directed to improvement of existing buildings and lands, but none toward construction of completely new buildings, nor purchase of additional property.

- Data will be collected on the outcome if a clients first choice of sites and dates are not available.

- Data on property usage, budget allocation for repairs & maintenance, will be shared with the membership on a regular basis.

- The evaluation period will begin when the site reservation system is shown to be working effectively.

- The evaluation period shall be three to five years in length.

- The final property decisions will be based primarily on the usage data.

Cognizant of the important role of camping as the signature activity of Girl Scouts of North East Ohio, and the degradation caused by a policy of preemptive neglect by certain legacy councils; priority in the council budget will be directed to outdoor programming at our camps during this trial period. To defray expenses and support member services, the camps should be used for additional programming: journey steps, volunteer training, service unit events during the week, etc. whenever possible. We recognize that with the increase in council membership, we are in a good position for such a comprehensive study.

Corey’s resolution was seconded – and ignored. Shortly afterwards, the Assembly was dismissed. Brent Gardner told a reporter in the lobby that the uproar inside the meeting was just a small, vocal minority. The silent majority of the council membership supported the board’s plan.

Member response

For the rest of the spring and the following summer, members wrote letters to the board, to the national office, to the media. Petitions were distributed. “Camp-In”s were held on the lawn of the council headquarters in Macedonia. The Board insisted that girls of the future wanted versatile spaces with science and computer labs. Protesters questioned how GSNEO, with its poor track record of online registrations and data collection, could think of trying to position itself as cyber and science experts. But anyone questioning the board property plan was discredited as nostalgic and emotional. The Board plan was “a done deal” for moving forward.

When it became clear that the board would not re-consider, a group of delegates led by Gwenn Kolenich and Roberta Riordan began investigating what actions were open through the official Girl Scout democratic process. Various experts were consulted and options weighed. One option was to impeach and replace the board. But fears of de-stabilization made that a last resort.

A parliamentarian told the delegates that the reason Corey’s resolution was ignored was that she had not followed the correct procedure. She should have motioned for a change to the agenda at the beginning of the meeting to allow “new business” to be discussed. Then she could have introduced her resolution. Roberta began studying parliamentary procedure. Gwenn reviewed the GSNEO code of regulations and found that a majority of the General Assembly could call a special meeting to take action on an issue. She began drafting a special meeting agenda.

The delegates affirmed that they would not demand that certain number of camps be kept. They just wanted the decision to be reviewed with the understanding that girls wanted to camp, and that camping had value. They wanted to have accurate usage data, realistic cost projections, and member input. They wanted it understood that although the council subsidized camping by nearly a million dollars per year, members in turn subsidized the council through $8 million of cookie sales in an $11 million annual budget.

There was no way for the delegates to independently check the accuracy of council-generated data other than internal consistency and the delegates’ own observations. Therefore, it was decided that the criteria for acceptance of a property plan would simply be approval by the General Assembly. Working with a lawyer, the delegates drafted two resolutions. One was an amendment that would require all future property sales to have the approval of 2/3 of the General Assembly. If the amendment passed, and the board refused to accept it, then the delegates would move to impeach. If the board showed themselves willing to accept the will of the majority, then they could stay.

However strong an amendment might be, it would not affect the plan that they had already announced. There would need to be a resolution addressing the immediate crisis. The general understanding of GS governance was that “delegates influence, the board decides.” In other words, the delegates could not tell the board what to do, but the board was obligated to consider the wishes of the delegates. In response to Brent Gardner’s statement that the majority of the members supported the board, they needed a clear statement that the delegates did not accept the board’s property plan. This statement was drafted as the first resolution:

The present Membership Delegates will vote on a resolution requesting that the Board of Directors immediately cease and desist all activities in connection with the transfer of any real property held in the name of the Girl Scouts of North East Ohio, until such time as any such pending, anticipated or planned transfers may be approved by a vote of two-thirds (2/3) of the voting members of the General Assembly participating and voting at a meeting held pursuant to Article II, Section 3 of the Code.

The delegates and other volunteers began circulating the request for the special meeting. About half of the needed signatures were obtained right away. The council office refused to provide contact information for the others to forward the request for signatures to them. The delegates were located one by one throughout the following summer.

As time passed, Roberta became concerned that they might not be able to find enough delegates to sign the special meeting request. She wrote a slightly different version of the amendment to submit for the regular meeting of the General Assembly in October. The Council Chief Operation Officer told her that she could not submit a resolution because the procedure for submission had not been established. Roberta submitted it anyway using the national procedure.

The 51st signature for the special meeting was obtained on September 29th. The signed request was delivered to the council office the next day. The board chair had 30 days to call the meeting and he chose to schedule it immediately prior to the regular Fall General Assembly on October 29th.

The formal call to meeting was mailed out from the council office which included the agenda of the special meeting and Roberta’s resolution in the regular meeting. As per usual, there was a single slate of candidates proposed for the Board of Directors by the Board Development Committee. The only way to have alternatives from the BDC slate was to nominate candidates from the floor. But GSNEO code required that floor nominations submit applications in advance with three endorsements from current assembly members. Pro-camp and pro-democracy candidates who had been rejected from the slate of board re-applied to be candidates nominated from the floor.

MEETING 2

Chairman Dan Bragg started the meeting by instructing the delegates that they could only speak once on each topic, for no more than one minute. Roberta objected, citing parliamentary procedure which permitted each delegate to speak twice for up to ten minutes each time.

Proponents of the resolutions reminded the Assembly that that they were asking for a realistic re-evaluation of a disastrous camp plan.

Opponents complained that they had been bullied by numerous messages and argued that only the board – not the average member- had the financial qualifications to make important business decisions for the council.

Debate proceeded until the chairman called for the Assembly to vote on the first resolution. It passed 52-35; 60% of the vote.

The quorum report just prior to the vote was:

12 Directors

1 Girl Director

6 Board Development Committee Members

5 National Delegates

63 Membership Delegates

With this clear message that the majority of the membership supported re-evaluation, the board finally had definitive information on membership opinion. But it made no difference. The vote did not change when it came to a permanent amendment to protect the rights of the members: 60% in favor. Not enough to pass an amendment which required a 2/3 majority.

Since the amendment failed, the question of board acceptance was moot, as was impeachment. During the regular meeting, Roberta presented a brilliant explanation for her version of an amendment. The vote was slightly higher in favor, but not up to the full 2/3 majority needed to pass.

Unexpected controversy rose during the election of board members. Although there were eight vacancies on the board, the chairman declared that only five seats were to be filled. Delegates pointed out that the code of regulations said nothing about restricting elections. Delegate Barbara Parkinson read the pertinent sections out loud to the Assembly. But the head of the BDC, the board chair, the parliamentarian, and the council lawyer all refused to allow a full election. Dan Bragg declared that any ballot with more than five names marked would be disqualified.

* * *

In the focus on the amendments and the dismay over the restricted election, the delegates did not immediately realize the significance of the vote on the first resolution. They had only asked that the membership delegates vote on it in order to give the board of directors clar knowledge of overall membership opionion. But instead, the chairman had directed the entire Assembly to vote on it. And the entire Assembly passed it.

What did this mean? True, it would have been stronger if one of the amendments had also passed. But if council democratic process had any value at all, then passage of this resolution to cease and desist from property sales without approval of the Assembly had to be considered as a valid directive. This was brought to the board’s attention.

The board refused to honor the successful resolution.

The members formally asked GSUSA to intervene - in the belief that the national organization would uphold democracy as the foundation of the Girl Scout movement. GSUSA refused because the request had not come from the council board or CEO.

The members then took the issue to court.

How the legal action played out

- The lawyer for the coalition decided against filing a class action lawsuit. The first thing he did was file for an injunction to prevent GSNEO from selling camps while a trail was pending.

- Three days in court and then the injunction was denied.

- Then GSNEO asked for a summary dismissal of the case. It was granted.

- The coalition appealed. he appeals court decided that they would not be able to hear the case because of a technicality.

- The coalition filed a second appeal. This time, the appeals court reviewed the case and ruled that:

- the 2011 GSNEO board election had indeed been improperly restricted, and there was enough of a basis to take the case to trial.

- GSNEO asked the coalition to meet for formal mediation. The coalition agreed.

- None of the GSNEO board came to the table, and the staff who represented were not prepared to discuss the issues.

- There was little point in going to trial to establish what the appeals court had already stated. Most of the camps had already been sold.

Was there anything that could have changed the outcome?

During Vision 2012, GSNEO received two generous offers for conservation easements that would have allowed them to maintain two of the camps. One was for Crowell Hilaka in Summit County offered by the Western Reserve Land Conservancy, which was a direct response to the camp's closure. The other was for Camp Lejnar in Lake County made by the Lake County Metroparks. This had been in the works for a long time. In both cases, GSNEO informed the donors that acceptance of such arrangements would "impair the integrity of the Vision 2012 process". Everything had to be put on hold until after the final decisions were made.

At about the same time that the conservation easements were being rejected, Camp Ledgewood broke ground for a new observatory. When members asked how a major new construction project fit in with the supposed "integrity of the Vision 2012 process", the GSNEO board and staff replied that they couldn't help it. They had gotten a grant for the observatory and had to use it.

Millions of dollars in conservation easements- rejected. New construction elsewhere- accepted. Member surveys strongly in favor of keeping camps - ignored. The evidence suggests that the camp decision was a forgone conclusion. The legacy councils that came to the merger with healthy bank accounts knew they would be allowed to keep their camps. As for the others: GSNEO invested much time and energy trying to give the appearance of careful judgments with member input. But it's likely that no amount of money, member support, or public opinion could have made any difference.

(Trefoil Integrity was the coalition of GS members, particularly delegates, across the northeast Ohio council who believed in the democratic process as outlined in the GSUSA constitution. In spite of being from different camps, they refused to compete with each other. Instead, they worked together trying to protect the rights of GS membership and trying to preserve outdoor experience as a basic part of Girl Scouting.)